A Day in the Life of Yevgeny Yevtushenko

7:57pm

A tall man (six feet, three inches) wearing a purple, single-breasted dinner jacket is coming toward us, waving the back of his hand as if to brush us all away from Gate Two. As he gets closer to us I notice that his jacket is actually neon-spattered with webs of pink. A total of seven gold-coin buttons are plugged into this web. Five gold buttons run down the man’s stomach to match the single coins on the ends of his sleeves. The other two can be glimpsed on the middle his side pockets, only if I shake my head—in disbelief—from side to side. His lapels are so wide that he could well fit into a 1930’s gangster film, provided the twentieth-century colorization experts were shot and killed, face-mashed into their damaged control panels during the movie’s opening scenes.

Some barren life I lead: it strikes me that I’ve never actually seen a tie-dyed suit before this moment.

“Must be the flight from Las Vegas,” says Patrick. “One day too long inside Caesar’s Palace and that’s what a man can turn into.”

“Salt Lake City,” I say, “and that’s our man.”

I am still holding up the book I’m using in lieu of a name card, when legendary poet, Yevgeny Yevtushenko sees us and waves at my prop like a tired, old friend.

“Yes, yes, is my book,” he says, “I wrote that.”

Patrick says nothing. The both of us are still standing outside the wooden, makeshift corral that Calgary International Airport resurrects before every Stampede season. Patrick’s face is leaning over the edge of the corral, staring at Yevtushenko’s pink pants—his nylon pink jogging pants—the kind that wrap up into a little ball and never see the outside world except on ski slopes or aerobic mats.

Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Russia’s “voice of the thaw,” published his first poem in 1949 at age 16, his first book three years later. He was the first Russian writer to speak out against Stalinism and by 1957 he was expelled from the Young Communist League because of his “individualism.” In 1961, his epic poem Baba Yar, inspired Shostakovich to write a symphony using Yevtushenko’s words. Another known fact: his public readings in Russia have been known to fill stadiums.

His new novel, Don’t Die Before You’re Dead is billed as “a contemporary epic that merges autobiography with fiction,” but Yevtushenko calls his book “a Russian borscht” of a novel that includes elements from every part of contemporary society.

“My nickname is Genya” he says, with a thick, pleasing Russian accent. He drags his mouth over the “Ge” of his name as if to speak French, and begin the phrase “je m’appell...” To my ears this sounds vaguely like “Je-Enya”—two words that might sound better stretched, then mashed together with benefit of a mouthful of Port. But after we get over these awkward, foreign introductions, he gives us the first of many plans: “Let us get out of this airport. I need something to eat.”

8:45pm

We stop by the side of the road, at Calgary’s “Lover’s Leap” to see the view of the downtown skyscrapers. The wind is cold; it shivers across the Bow River and climbs up the cliff toward us. Patrick explains the absence of submarine races in Alberta and Yevtushenko—Genya—seems genuinely interested in this dialogue. He’s turned away from the wind, focusing his eyes on Patrick’s mouth, watching the words come out, one at a time, until I notice Patrick has stopped speaking.

9:30pm

“I want to try your Canadian wine,” he says. “Usually I prefer the Italian wines, but you cannot buy Italian wine outside of Italy. You cannot even believe the labels that they glue to the outside of their Italian bottles. Listen to me: this is true. I have many Italian friends. I can tell you. The Italian wine that you buy outside of Italy is from Albania.”

We settle on a bottle of Okanogan red.

When the bottle arrives, Yevtushenko waits for the moment itself to settle, when all eyes are on him, then judges the quality of this Canadian wine, rolling the juice in his mouth.

Another moment passes.

Finally: “Is good wine,” and we smile together.

Yevtushenko reaches for the book I’m still holding, a copy of his novel. We’ve done the requisite book exchange and despite holding his glass of wine, firmly in one hand, he’s suddenly flipping wildly through my book, looking for something, he says, “that is Siberian custom between writers.”

“We must discover our destiny,” he says, “I will go first.”

Still with the glass of wine in hand, he flips through the book and looks up at the ceiling. Our eyes follow his until we realize he is searching for a thought, not a sign from God.

“Page 107,” he says finally, “line 7.”

He counts down the page. “Yes,” he says, “yes, yes, is good destiny I think. Listen. This man. Celli, who is this man?”

“A miner.”

“A miner. Good. A working man. I too am a working man. A man of the people. From Celli’s breath comes these words. I ride on the breath of the ordinary man. Is good destiny.”

Smiling broadly, Yevtushenko breaks the book’s back with one hand, and pours wine across the inside of the book. The edges of the pages bleed wine over the table, then he moves the book to the side and sprays a stripe of wine on the floor as if rinsing a paint brush.

“Is very good destiny,” he says.

Our waiter doesn’t notice the remains of our destinies dripping from the tablecloth, so I am inclined to agree.

By the time we leave the restaurant we are fast friends, I think. Italian food and cheap wine splashed over several books will make friends out of any group of people, and Genya grasps the two of us as we walk toward his hotel.

“I know you like my twenty-one fingers,” he says. “Is old Siberian expression.”

It’s the kind moment I’ve heard about from other writers, during other Yevtushenko visits to Canada: John Metcalf has just spoken a few words of Russian to welcome Yevtushenko to the table, and Genya is so pleased to hear the words, the courtesy shown, that he jumps up from the table, in the crowded room, to hug a grown man. The room grows quiet. Nobody puts down a fork. No one touches a glass. And that is when Yevtushenko suddenly notices the silence, and the crowd’s stares.

“We are not queers!” his voice booms, gripping his new friend more securely, “we are Slavs!”

Patrick and I leave him in the lobby after giving him a copy of tomorrow’s itinerary.

“Four interviews tomorrow? Is too much. We must call this woman directly, this publicist, what is her name? Give me her number I will call her myself immediately. Is impossible for one man.”

Next day, 9:00am

Gzowski, CBC Radio interview, speaking on the fall of Communism and the division of the USSR:

Y: “Nothing unites people more than a common enemy and nothing divides people more than a common victory.”

G: “Have you written too much?”

Y: “Is too late to discuss about this. I published 135,000 lines of poetry. Seventy percent of this is—I’m trying to find polite word—is rubbish. But sincere rubbish.”

10:00am

Fax Transmission to Colonel R_____, Base Commander

Number of pages including this page: 1.

Dear Colonel R_____,

Having spoken to your secretary yesterday afternoon, I am writing you to request some military equipment—a camouflage jeep or (hopefully) a small armored vehicle for the literary event of the year... There is enough space for a jeep or tank to sit out front, and I could arrange for chairs to be placed in front of the vehicle, with Yevtushenko standing on the tank as a symbolic podium for democracy...

Still no word from the military. My fax, I believe, will never be answered by written correspondence, other than getting me on a list somewhere. For the record: Yevgeny Yevtushenko is the only man whom I would consider getting a tank for, and I am not particularly interested in asking for a tank ever again. Certainly not a large tank. Nothing garish. I only wanted a small one to sit out front of the shop, something to commemorate Yevtushenko’s efforts in freeing Mikhail Gorbachev from the 1991 attempted coup.

If the rain lets up, I do have the phone number for a friend of a mechanic’s cousin who has a couple of tanks I can borrow (amazing what people have sitting in their backyards).

But going through so many middle-men somehow makes me nervous. Such offers are suddenly appearing every way I turn: a Russian businessman calls to offer me his old service uniform, a rifle and his daughter (strictly for translation purposes), should I have use for these things.

The catch: “It would be very pleasurable evening to meet Mister Yevtushenko,” he says, “for private dinner with very few people.”

At this moment, only the weather seems capable of confirmation—not the tank, not the mechanic, not the dinner—only the dark clouds that seem bent on raining-out this military exercise. I look up at the sky for the twentieth time today and finally decide on an indoor reading.

11:00am

CBC Television Interview, Alberta News Hour, taped in the bookstore, to be aired nationally the next day:

Yevtushenko: “When you choose between your conscience and fear, what do you choose, conscience or fear? I choose conscience. When I protest against our tanks in Czechoslovakia I remember I was ready to be arrested. I overcame my fear. A little bit I underestimated my popularity because they just couldn’t arrest me.”

The interviewer pushes him further along on the subject of fear, and toward the attempted coup in August 1991. He was there, she says, on the balcony of the Russian parliament building, using his poetry to defend freedom.

Cut to film coverage (day shot) showing a wet crowd standing with umbrellas beside a tank and a row of flowers, placed next to the road. Camera pans up. Cut to night shot of tanks, lit from underneath as if on fire. Soldiers walk calmly beside the tanks down a narrow Moscow street. Cut to gloomy day shot. A white flag is tied to a tank’s radio antenna, six people climb over the tank, as if searching for a vantage point to see something out of camera range.

Cut to parliament building, day. A mass of Russian fur hats, incomprehensible Russian signs and tri-coloured flags move as if in slow motion. Pan upward, to balcony shot: there’s Yevtushenko in a dark blue overcoat, a red scarf tucked into his collar. He leans into the microphone and his jaw disappears just as the translator’s words cover Yevtushenko’s voice: “We are all for freedom, but not for the freedom of murderers.”

Yevtushenko looks up.

The poem ends:

...the Russian Parliament

like a wounded marble swan of freedom

defended by our people

swims into eternity.

11:30pm

Camera cuts to the crowd below.

One hundred thousand hands rise up, a sea of open palms.

Cut back to CBC interview, bookstore.

Yevtushenko admits: “I was scared. Even my wife was screaming. She was calling me stupid. She was screaming something like that: Look! If they’ll kill you do not come back to our house! You know she said this, she became crazy because she was worried about me.”

12:00pm

Genya returns to the bookshop with Marilyn Wood, publicist, riding shotgun. His energy is on the upswing, despite the fact she has changed the day’s itinerary and actually added an extra interview. She fit him into three separate interviews by keeping him in the CBC building and having the hosts move around him. Coast-To-Coast Newsworld, the Homestretch, a quick plug for CBC Sunday Arts program, then back to the television studio, then back to Kensington to meet for lunch.

Yevtushenko smiles broadly.

Across the street at an Italian restaurant that shall remain nameless (I have since been banned from this place for life), Genya arranges himself at the table, while Marilyn, two Russian professors and myself make the introductions.

We decide on an Italian wine. “Is enough to try the Canadian grapes yesterday,” he says. “Now we must extend our experiences to another country.”

A soup arrives and seems to scald his mouth with the first sip.

“Pepper!”

“Pepper?” I ask.

“Pepper, pepper, PEPPER! Is full of pepper! I’ve been to Italy many times,” he says. “And pepper is always on the table, not in the recipes.”

Genya sends the failed offering back to the kitchen, then two more soups come and go, then three entrees, a bowl of tortellini and finally a plate of spaghetti marinara. Rocco the chef, an imposing girth of a man, comes out of the kitchen with Yevtushenko’s plate in his hand. The plate is tilted in Rocco’s hand so the food seems ready to slide off the side or smash into the side of Yevtushenko’s smiling face.

“Pepper,” he says.

“I don’t put any pepper in my food. I don’t know what your problem is.”

It strikes me strange both men are speaking a foreign language, English, yet both would probably be happier to discuss this matter in Italian.

“No pepper in the pasta?”

“No pepper in the pasta.”

“No pepper in the vegetables?”

“Not in the vegetables.”

“What about the sauce?”

“I make the sauce myself. There is no pepper in the sauce.”

“The tomato sauce?”

“It is from a can.”

“Ah,” says Yevtushenko, nodding his head to the rest of us, “the tomato sauce.”

Rocco fumes silently for a second, slightly derailed, then recovers admirably with the firm statement: “I don’t put any pepper in this food!”

People are watching.

Yevtushenko pauses for effect, then announces to all: “I have tried all of these dishes you have on your menu. I can tell you, the only thing I have found here without the taste of pepper is the wine!”

Rocco seems to totter slightly to the left of our table while Yevtushenko raises his hand to the side of his head and waves his open fingers to shrug off this sudden comprehension.

“The canned tomato sauce,” he says.

With a moment of triumph safely secured, Genya shakes his head and graciously admits: “Maybe it is just me. Maybe I am crazy.’

“I think you are crazy,” says Rocco, stepping closer to the table. There is a moment when I think this could well turn into an international incident. The headlines flash in front of my eyes: Russian Poet Brained In Restaurant, Victim Forced To Eat Weapon.

The spaghetti slides a little further to the side of Rocco’s plate while Yevtushenko looks at Rocco, a confident smile seems to wrinkle the edges of his blue, Siberian eyes. He is, I think, genuinely “bemused.”

Rocco takes another step toward us.

“You are absolutely crazy,” he says.

Enough, I say: “basta.” I raise hand, but I’m too far away from Rocco to stop his approach. I want to rise to my feet and say something like, “This man is my guest,” but the moment quickly disappears when he notices his wife leaning into his field of vision. All Rocco’s Italian sensibilities seem to kick into gear, and with a mutter I can’t understand our “gentle host” shrugs, retreats back to his kitchen.

A white plate appears seconds later, with a pan-fried chicken breast upon it. No garnish, just a slightly brown chicken breast which Yevtushenko gobbles down his throat before he leaves the table with Marilyn, the both of them already ten minutes late for their next set of radio interviews.

Years later, the Russian professor will take a trip to the Ukraine, and describe this lunch, and the reading, in detail. Nearing retirement, he will speak frankly about his lunch with Yevtushenko. He will admit that he has a heart and lung condition that makes for a—well, it’s not an interesting story—but when the cold air begins, any change of weather, he has only to take one whiff of it and he is bedridden for a week. So Dr. Struc speaks bluntly. He believes he has little time left, so he tells his foreign students the truth.

“There were dozens of old women with looming breasts and as Yevtushenko walked up the stairs, he brushed their tits with his hands—the back of his hands, and then the palms—as he danced them up the stairs of the bookstore. It was his privilege! His right: don’t you see? His duty! This was his homage, paid in full, as an Eastern bloc writer. It was his homage to the fat of the land, and he grabbed it with both fists.”

The students in Ukraine, who associate Yevtushenko’s name with their parent’s tired descriptions of a distant Cold War, will recoil in shock.

7:00pm

The Russians are coming. More Russians than I ever knew existed in southern Alberta. Some of them pound on the window. When I open the door I am hit with a dozen questions all at once.

“Yevtushenko. He’s coming here? Here? To this place? You’re sure?”

“Yes,” I say, “I’m sure.”

“Where is he now? Where is he staying? Have you seen him yet?”

More Russians are coming. They are arriving early, standing outside in the rain while we stack chairs on the main floor and the second floor. There’s a problem with the main microphone, but the cordless one is working fine.

7:15pm

The shop is chock-full of Russian speakers and the sound of English is fading quickly. Over 300 people wedged into a 1,800 square-foot bookshop. Over 100 chairs are bought, rented or borrowed from neighboring bars. The rest of the people are standing, already shifting themselves into some kind of ebb and flow. They seem to take turns breathing, so they don’t bulge the walls out any more than necessary. One small, cannonball of a woman knocks me over by the stairs, muttering to herself on the way up. Two steps later, she looks back at my wincing face, and answers the question I was too afraid to ask:

“You think there are no more seats left upstairs for me? ME? I am small and I am Russian, you are not Russian, I am Russian. And I know Yevtushenko better than you and I am going upstairs.”

When I put up my hand on the rail, grasping for some transitory sense of balance, she takes the gesture as license to move up the stairs and disappear into the crowd.

7:10pm

Still no Yevtushenko.

7:20pm

No Genya

7:29pm

An old man stops me as I’m going to the back door to check yet again for Yevtushenko. “There are too many people here,” he says. “You should have had this event in a different place. You should have reserved seating. Tickets. This is a terrible event.”

“Wait,” I beg him. “Wait until you’ve seen him. He’ll be here.”

He seems leery of this suggestion.

“Talk to me after the event, “ I say, “I want to know. Talk to me after.”

7:30pm

If there is an after. Still no Genya.

7:40pm

Genya enters through the back door with a growl.

“Is there some place quiet we can go—I need to be alone.”

I nod quickly and take him downstairs before any one can see him.

“Is probably no one here for this reading,” he says, “just a couple of babushkas in audience. No one.”

To make this moment worse, he adds: “You cannot believe the day I’ve had. Very bad news from my American publisher. I am not feeling well.”

In a feeble attempt to change the subject, I say that his suit looks quite good. It is alive, I tell him, festive.

“This?” he asks, the Russian equivalent to this old thing. “I make myself,” he says. “One day I was wondering how to make a suit, what is like to make a suit. So I try. Two weeks it took me.”

Yevtushenko smiles and I imagine this impossibly tall Siberian man crouching over a black machine, fashioning a neon outfit for a trip to Las Vegas he may never take.

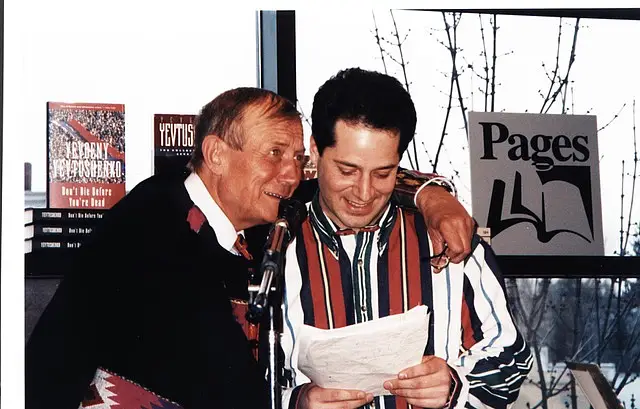

8:00pm

The reading. We trade off, reading sections of his poems, four stanzas at a time, English first, then thick, glorious, incomprehensible Russian, drooling down his mouth, the words swinging like Tarzan over the podium. There is no way I can match his movements, the hand flourishes of this man. Even in my thankfully brief moments on stage, Yevtushenko’s presence is too commanding not to watch. I can just glimpse him in the corner of my reading space, bouncing from side to side, a tennis player getting ready to jump on the tape as soon as the ball is served.

I watch this man grow large, loom in front of his audience to cinematic proportions, feeding off their enthusiasm with every poem he gives them. A natural actor, he performs his poems, line by line, picking one woman in the audience after another, each woman a balcony he hopes to climb with his outstretched, open hands to the next balcony. The passion of this opera grows and Stenka Razin is on the verge of coming through the door and the room seems to pulse with KGB suggestion, blackmail and sweet, Soviet nostalgia, and suddenly Yevtushenko (the great Romantic) seems to reach the highest balcony in the room and he ends a stanza by kissing a woman’s hand. The next poem it is an arm, then a shoulder, a cheek, Patrick’s stomach, a young woman’s open palm, and in one case: the lips. A babushka faints, falling into her chair and I finally understand the Beatles’ frenzy.

Genya moves on. We eventually descend the stairs, to visit the main floor because, he says, “this is Democracy. We cannot favour one group over another,” and the crowd parts for him to pass.

I turn to follow him and someone grabs my sleeve. It’s the old man. Tears fill his eyes. The moment hangs—neither of us speak—then he smiles and pushes my arm away, prodding me down the stairs to follow Yevtushenko’s poems.

9:00pm

Between these poems, there is commentary on all things Russian and literary:

“The social stage appeared in 1953, some slim, fragile figures of some girls and boys—almost teen-agers—my generation, they began very uncertain how to talk about the necessity of freedom of speech, writing their words against anti-Semitism, chauvinism. That was role of my generation. We were at that time...there was not any kind of dissident movement, because all potential dissidents were already killed. So we were one. We were everything during those years. We were brought up under very hard censorship. And, you know, to live under this house censorship, it’s like, oh, it’s like breaks your bones or it fucks you forever.

“And probably, in a way—paradoxically—sometimes censorship is very helpful for metaphorical language of poetry. Yes, is true, but unfortunately our censors, they were learning quickly too. They are greatest readers in the world because they were reading between lines beautifully.

“And afterwards it was time of goodness mixed with hopes. Our allusions [illusions?], some of them were broken. It was a beginning of new era in Russia.”

9:20pm

“In Russian this (poem) rhymes. You know that is tragedy. Because in our poor Russian language we have exactly twenty-four times more possibilities for new, fresh rhymes than in English. It doesn’t mean that I underestimate English; because I admire some English words. For instance: I was trying to translate one beautiful, irresistibly charming English expression, back-seat driver, but doesn’t work in Russian.”

9:45pm

“I was always writing about love and politics. I understand if writers involve too much in politics it makes his style, his soul, drier. It is what happened with me once, I remember:

“For three years and half I was member of parliament. One general insulted me—another member of parliament. Let’s have all members of parliament insult each other. Probably only Canada is the exception.

“So he insulted me and I was preparing my answer to him. And Gorbachev didn’t give me a word. He could see I was furious. And fury is very bad adviser, always. It was the same the next day.”

“Tomorrow,” he said, “you must wait for tomorrow.” And finally, after I hear this word tomorrow, again and again, I ask Gorbachev directly: “When will be this tomorrow,” I ask him. “When?”

“Your tomorrow,” he said, “will be tomorrow.”

“Probably it’s symbolic.”

“So I was working on this political speech, writing, shaping it, trying to be very polite and use poisonous, sarcastic remarks... and I heard some steps behind me.”

“I ask: who is it?”

“Your wife, Marsha.”

“Do you have some new information?”

“She said, Genya, are you getting crazy? Yes, I do have some news. I have very important news for you. I just want to tell you how I love you before I go to sleep now.”

“She began to laugh and I began to laugh, because I understood that being involved in politics I just lost the sense of simple human feelings. All politicians they are fighters and when you fight, your skin could be transformed into a rhinoceros skin, a kind of shield. Of course, its shell saves you from daggers, but it doesn’t give you possibility to feel just human touch. And this is politics.

“It is very dangerous for writers to concentrate on politics, but at the same time I could not respect writers who were completely indifferent to the politics. I am absolutely sure if they are indifferent to the politics they are indifferent to the people. Politics deal with the people. Politics destroy the people, humiliate people.

“It’s the duty of the writers to protect their readers. And so sometimes I know those such (writers) who declare a beautiful indifference to politics, snobbishness. They declare sometimes very high-flown style. This is nothing more than cowardice, hidden cowardice. They are just cowards in my opinion.”

10:00pm

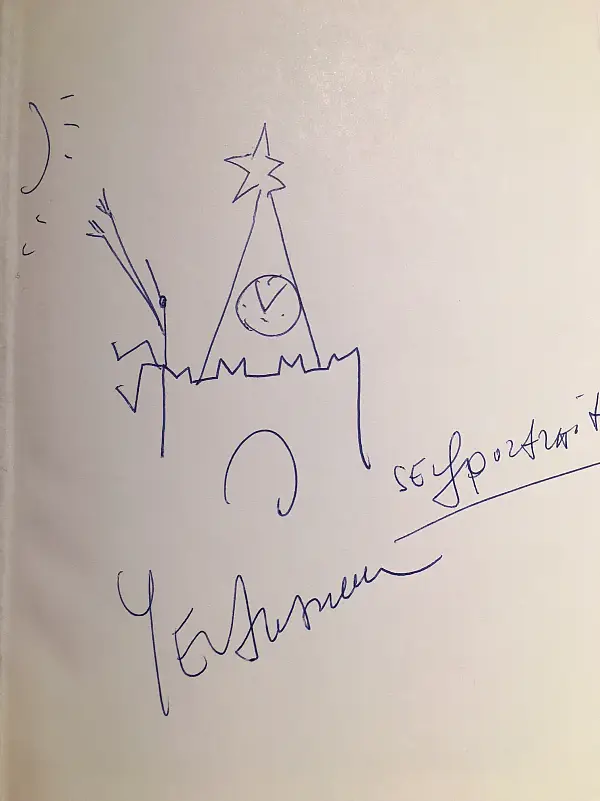

A selection of personal quotations Yevtushenko writes into other people’s books:

--Judy, you say my book exhausted you. I only wish I could exhaust you in some more delicate manner.

--I bless your destiny.

--Self portrait (drawn, showing a stick man on two spires, reaching for the sun).

--With my great faith in you.

--With my best feelings.

--To Mona. From her unsuccessful admirer.

--To Jill & Rob. From a couple who were engaged before they were born.

--I am sure that you will let down neither your friends, neither yourself.

--To Patrick Rengger, with my brotherhood forever.

--With my respect and belief into your great future.

--I would like if the wheel of the 21st century will be in the hands of young people like you.

--To Jennifer, with admiration & with a hope that we will be friends forever. Good luck with your first novel.

--For Yevtushenkologist Number 1

A note, left behind, from a visiting librarian: A rainy night. I was wet from head to toe as I didn’t wear a coat and almost late. The crowd was surprisingly large but I squeezed into a teeny spot on the main floor right behind a pillar. The poster photo depicted a clean-cut fellow smiling in a suit and tie. That did not prepare me for the jacket! My God the jacket! Like the Pied Piper or Joseph and his coat, like some Tibetan rug on his back. He was a complete beatnik in this jacket, and he never stayed still! He gestured as he moved through the crowd waving his arms, looking and sounding like a player from some Medieval drama. That was great performance! Then he came right over to me and put his arm around me at a particularly poignant moment, spoken in Russian which I couldn’t understand, and he beamed a big smile at me, up-close and personal. A lot of people laughed so it must’ve been funny. Then he disappeared upstairs... After the reading the throngs remained but even tighter around this man, vying for his attention upstairs, mostly largish Russian middle-aged women. In front of me in line to get books signed was a youngish guy, looked like a uni. student. When this kid approached Y, Y asked him, what was his profession? A student, but he just wanted Y to sign a poster as he didn’t have the money for a book. At this Y looked shocked, jumped up and quickly grabbed a book from the display table, waved it in the air and announced that he was buying this copy for his friend and proceeded to sign it with a flourish. Then it was my turn and the three Russian women behind me were getting distinctly restless and their voices increased in volume and urgency. Y asked me, what is your profession? I’m a librarian, I said. Y exclaimed that was the noblest of professions and how worthwhile to society it was, etc., etc. and he thanked me for coming on such a rainy night. I had two books for him to sign, I wanted the new book for my father’s birthday on the 21st of May, so he signed it and the other book I brought. I didn’t get the chance to read the inscriptions then as the women behind were physically ‘easing’ me to the side and addressing Y from behind and thus my time before greatness was up! He signed my 1962 edition of ‘Selected Poems’ with an orange thorny branch on the cover thus: ‘To Karen with my deep respect for your profession. Y 1995.’ The new book was signed rather oddly thus: ‘For Jim (my father’s name), from your daughter Karen, and her admirer, Y.’

10:45pm

Answers to selected questions:

“The French say that translations are like women. If they’re beautiful, they are not faithful, and if they’re faithful, they can’t be beautiful. I think this is not true about women, but is sometimes true about poetry.”

11:45pm

Glancing at an attractive CBC reporter, then to me, sitting across the table at Razzbarry’s I & Bar:

“She is volcano, she is Canadian volcano.”

Looks back to the woman.

“Are you active or passive?”

Genya’s thick accent too fast for her, she looks to me for the translation.

“He wants to know if you are an active volcano or a passive volcano.”

“Passive, I think,” she says meekly.

A moment later he is up on his feet. “I must drink to your beauty the Russian way! Give me your shoe!”

Her face turns red and she crouches further into her chair. She tries to hide her breasts between the wings of her shoulders and make herself disappear from this sudden attention.

“No, I can’t. Oh my god, no. I’ve been wearing these boots all day long.”

I look down to the floor and her ankle-high boots move closer together, hiding underneath her seat.

“Give him the shoes,” I say, “just give them to him.”

More prodding from the others at our table and the woman finally takes off her shoe and hands it to Genya.

He calmly puts his glass of vodka in the heal of the shoe and the rim of the glass disappears within the ankle’s holster. Yevtushenko stands up, silver hair ruffled (intrusive authorial insert), and announces to the whole bar: “This woman is Canadian volcano. I drink to her beauty.”

No one outside of our table can see the glass hidden in the boot, and while I marvel at the man’s ability to discover a woman’s ankle boots in a dark bar at fifty paces, Genya knocks back his head and completely drains her shoe.

Time unknown

Later that evening, there follows a postscript to this story, entirely hearsay and probably fiction. The details can be left out of this serious chronology of events because they are fuzzy (at best) and the source is modest (at her best). The rumour: another bar, another bottle of champagne, another woman, perhaps. There is a spurned invitation to visit his hotel room. Perhaps. The words:

“You Canadian girls are spoiled. Just drop me off at the nearest cat house. Before you do... can I have your address?

An address is given. A reciprocal address asked for.

“You ask a lot for a woman who is not a lover.”

A counter-postscript, next day:

Yevtushenko emerges from the Palliser Hotel, late for his flight. A sly grin spreads across his face as he admits that he was up late last night. When Marilyn Wood goes to check him out, she learns that an admirer—from last night’s reading—has paid for his hotel room. Genya blushes, coyly: a difficult feat for a 62-year-old Siberian man.

10:00am

Genya has lost his plane ticket. Marilyn Wood tries vainly to get him on the flight, then waits with him for the next flight to Vancouver to appear on the airport screen in the departure room outside Gate Two.

“I think I am the most difficult author you have ever worked with, am I right?” he asks.

She nods and Genya beams.

“I must tell you this Marilyn Wood: I will start my next novel before the plane even leaves the ground, only so I can come back to look at your legs.”

11:10am

Flight 649 leaves the ground and Calgary, the entire city—in unison—breathes out, exhales as though a great weight has indeed lifted. And somewhere to the west, another Canadian city prepares itself—unknowingly—for another day in the life of Yevgeny Yevtushenko.

How should we begin our song,

How should we end it?

We shall begin with conversations,

We shall end with a kiss.

--Old Russian Folk Song